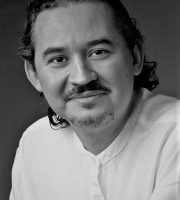

by Tomás Q. Morín

My brothers wait for me with cigars in their mouths,

debating the price of cabbage, the virtues of sleep

and my sisters having just arrived, hang their shawls

in the hallway and then sit and redden their faces

over white cups of tea. The train whistles

and the sleeping boy beside me just stirs

long enough to touch his father’s leg, to point

out the window at the large flocks of men

swinging their picks, spading their way

to the noiseless center of an imagined market

in Beijing where they will buy the best silk

their good looks can get and then rose their cheeks

until they look like grandmothers on holiday

in the Near East.

Beyond the men, in the smoky

clods of dirt I can see the lost children of this land

sneaking behind the silent showers to peek

at the concrete and its people. I consider

how long their eyes wandered before they turned

and took chalk to paper, coal to wood.

How would you see the world after that,

would the night teach you anything about comfort,

would you still marvel at your red-faced mother

pulling her clay head from the mouth of an oven,

her hair overcome with the smells of new bread?

A girl drops her chalk, bends and picks up

a long feather of smoke with her nose

and then begins to pity everything from the black

throats of chimneys to the huffing trains

logging through the countryside the baked bones

of her fathers and mothers.

I brood and mouth

the words of a question I cannot ask, cannot

voice to the unclean air: O little ones, would you have

looked any longer or moved the chalk any slower

if you had known that one day you’d be loved again

and again by the words in a book or that I would crawl

under your sky on the morning of my birthday,

bundled tightly in the seat of my car, your drawings

in my lap and on the floor between my feet

the last pies—one apple, one cherry—my mother

made now beginning to tear their metal faces?

Last updated February 23, 2023