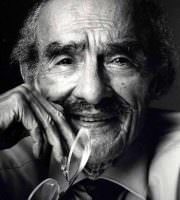

by Pedro Mir

1

There once was a virgin wilderness.

Trees and land without deeds or fences.

There once was a perfect wilderness.

Many years ago. Long before the ancestors of our ancestors.

The plains would play with galloping buffalo.

The endless coastlines would play with pearls.

The rocks let loose diamonds from their wombs.

And the hills played with goats and gazelles . . .

The breeze would swirl through clearings in the woods

heavy with the bold play of deer and birch trees

filling the pores of evening with seed.

And it was a virgin land filled with surprises.

Wherever a clod of earth touched a seed

all of a sudden there grew a sweet-smelling forest.

At times it was assaulted by a frenzy of pollen

squeezing out the poplars, the pines, the fir trees,

and pouring out the night and landscapes in clusters.

And there were caverns and woods and prairies

teeming with brooks and clouds and animals.

6

O Walt Whitman, your sensitive beard

was a net in the wind!

It throbbed and filled with ardent figures

of sweethearts and youths, of brave souls and farmers,

of country boys walking to creeks,

of rowdies wearing spurs and maidens wearing smiles,

of the hurried marches of numberless beings,

of tresses or hats . . .

And you went on listening

road after road,

striking their heartstrings

word after word.

O Walt Whitman of guileless beard,

I have come through the years to your red blaze of fire!

9

For

what has a great undeniable poet been

but a crystal-clear pool

where a people discover their perfect

likeness?

What has he been

but a deep garden

where all men recognize themselves

through language?

And what

but the chord of a boundless guitar

where the fingers of the people play

their simple, their own, their strong and

true, innumerable song?

For that’s why you, numerous Walt Whitman, who saw and ranted

just the right word for singing your people,

who in the middle of the night said

I

and the fisherman understood himself in his slicker

and the hunter heard himself in the midst of his gunshot

and the woodcutter recognized himself in his axe

and the farmer in his freshly sown field and the gold

panner in his yellow reflection on the water

and the maiden in her future town

growing and maturing

under her skirt

and the prostitute in her fountain of gaiety

and the miner of darkness in his steps beneath his homeland . . .

When the tall preacher, bowing his head

between his two long hands, said

I

and found himself united with the foundryman and the salesman

with the obscure traveler in a soft cloud of dust

with the dreamer and the climber,

with the earthy mason resembling a stone slab,

with the farmer and the weaver,

with the sailor in white resembling a handkerchief . . .

And all the people saw themselves

when they heard the word

I

and all the people heard themselves in your song

when they heard the word

I, Walt Whitman, a kosmos,

of Manhattan the son . . . !

Because you were the people, you were I,

and I was Democracy, the people’s family name,

and I was also Walt Whitman, a kosmos,

of Manhattan the son . . . !

15

And now

it is no longer the word

I

the accomplished word

the password to begin the world.

And now

now it is the word

we.

And now,

now has come the hour of the countersong.

We the railroad workers,

we the students,

we the miners,

we the peasants,

we the wretched of the earth,

the populators of the world,

the heroes of everyday work,

with our love and our fists,

enamored of hope.

We the white-skinned,

the black-skinned, the yellow-skinned,

the Indians, the copper-skinned,

the Moors and dark-skinned,

the red-skinned and olive-skinned,

the blonds and platinum blonds,

united by work,

by misery, by silence,

by the cry of a solitary man

who in the middle of the night,

with a perfect whip,

with a meager wage,

with a gold dagger and an iron face,

wildly cries out

I

and hears the crystal-clear echo

of a shower of blood

that relentlessly feeds on us

ourselves

among the docks receding in the distance

ourselves

below the skyline of the factories

ourselves

in the flower, in the pictures, in the tunnels

ourselves

in the tall structure on the way to orbit

ourselves

on the way to marble halls

ourselves

on the way to prisons

ourselves . . .

17

Why did you want to listen to a poet?

I am speaking to one and all.

To those of you who came to isolate him from his people,

to separate him from his blood and his land,

to flood his road.

Those of you who drafted him into the army.

The ones who defiled his luminous beard and put a gun

on his shoulders that were loaded with maidens and pioneers.

Those of you who do not want Walt Whitman, the democrat,

but another Whitman, atomic and savage.

The ones who want to outfit him with boots

to crush the heads of nations.

To grind into blood the temples of little girls.

To smash into atoms the old man’s flesh.

The ones who take the tongue of Walt Whitman

for a sign of spraying bullets,

for a flag of fire.

No, Walt Whitman, here are the poets of today

aroused to justify you!

“Poets to come! . . . Arouse! for you must justify me.”

Here we are, Walt Whitman, to justify you.

Here we are

for your sake

demanding peace.

The peace you needed

to drive the world with your song.

Here we are

saving your hills of Vermont,

your woods of Maine, the sap and fragrance of your land,

your spurred rowdies, your smiling maidens,

your country boys walking to creeks.

Saving them, Walt Whitman, from the tycoons

who take your language for the language of war.

No, Walt Whitman, here are the poets of today,

the workers of today, the pioneers of today, the peasants

of today,

firm and roused to justify you!

O Walt Whitman of aroused beard!

Here we are without beards,

without arms, without ears,

without any strength in our lips,

spied on,

red and persecuted,

full of eyes

wide open throughout the islands,

full of courage, of knots of pride

untied through all the nations,

with your sign and your language, Walt Whitman,

here we are

standing up

to justify you

our constant companion

of Manhattan!

...

Last updated October 23, 2022