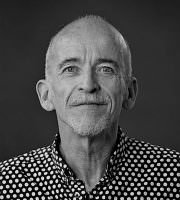

by Mark Doty

His music, Charles writes,

makes us avoidable.

I write: emissary of evening.

We’re writing poems about last night’s bat.

Charles has stripped the scene to lyric, while I’m filling in the tale: how,

when we emerged from the inn,

an unassuming place in the countryside near Hoarwithy, not far from the

Wye,

two twilight mares in a thorn-hedged field across the road—clotted cream

and raw gray wool, vaguely above it all—

came a little closer. Though

when we approached they ignored us and went on softly tearing up audible

mouthfuls,

so we turned in the other direction, toward Lough Pool, a mudhole scattered

with sticks beneath an ancient conifer’s vast trunk.

Then Charles saw the quick ambassador fret the spaces between boughs

with an inky signature too fast to trace.

We turned our faces upward,

trying to read the deepening blue between black limbs. And he said again,

There he is! Though it seemed only one of us could see the fluttering

pipistrelle at a time—you’d turn your head to where

he’d been, no luck, he’d already joined a larger dark. There he is! Paul said it,

then Pippa. Then I caught the fleeting contraption

speeding into a bank of leaves,

and heard the high, two-syllabled piping.

But when I said what I’d heard,

no one else had noticed it, and Charles said, Only some people can hear their

frequencies.

Fifty years old and I didn’t know

I could hear the tender cry of a bat —cry won’t do: a diminutive chime

somewhere between merriment and weeping,

who could ever say? I with no music to my name save what I can coax

into a line, no sense of pitch,

heard the night’s own one-sided conversation.

What to make of the gift? An oddity, like being double-jointed, or token

of some kinship to the little Victorian handbag dashing between the dim bulks

of trees?

Of course the next day we begin our poems.

Charles considers the pipistrelle’s music navigational, a modest, rational

understanding of what I have decided is my personal visitation.

Is it because I am an American I think the bat came especially to address me,

who have the particular gift of hearing him? If he sang to us, but only I

heard him, does that mean he sang to me?

Or does that mean I am a son of Whitman, while Charles is an heir of

Wordsworth,

albeit thankfully a more concise one?

Is this material necessary or helpful to my poem, even though Charles

admires my welter

of detail, my branching questions?

Couldn’t I compose a lean,

meditative evocation of what threaded

over our wondering heads,

or do I need to do what I am doing now, and worry my little aerial friend

with a freight not precisely his?

Does the poem reside in experience or in self-consciousness

about experience? Shh,

says the evening near the Wye.

Enough, say the hungry horses.

Listen to my poem, says Charles.

A word in your ear, says the night

Last updated December 21, 2022